| U.S. tycoon had major role in defeating Walker | |

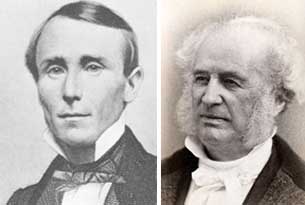

| SOURCE: AMCostaRica.com - April 4, 2013 April 11 is the celebration of the Battle of Rivas that immortalized Juan Santamaría as a Costa Rican national hero. That is why there is a statute of Juan Santamaría at the international airport that bears his name and in the central park of Alajuela, his hometown. There ought to be a statute of U.S. businessman Cornelius Vanderbilt, too, because if Juan Santamaria's brief and fatal action to torch an enemy stronghold is memorable so should the extensive support provided by Vanderbilt and his agents. As is true with most of human history, the actions that resulted in the Costa Rican invasion of Nicaragua and the battle in 1856 are more complex than that which is taught to school children. In fact, much of the dispute was about money. Walker from Tennessee wanted to run his own country. He tried to rule Baja California but was defeated. He lived in the age of U.S. expansion. If Walker sought fame and an entry in history books, Vanderbilt wanted money. Rising from a young ferry boat operator in New York, he saw shipping and transportation as his cash cow. That's why when gold turned up in California he pioneered routes that could carry the 49ers west. A principal route was through southern Nicaragua. Current President Daniel Ortega is trying to recreate the route Vanderbilt's Accessory Transit Co. had in the early 1850s. Travelers would go by steamer from the Caribbean west on the Río San Juan and eventually to Lake Nicaragua. Then after a brief land crossing at San Juan del Sur, they would board a California-bound steamer on the Pacific coast. Walker accepted an invitation from Nicaraguan president Francisco Castellón to provide aid in that country's civil war in 1855. He became de facto leader of the country as the nation's military commander when he defeated the conservative forces opposing Castellón. While Vanderbilt toured Europe on his yacht with his family, his employees in Nicaragua conspired with Walker to take over the transport concession. That's when Vanderbilt threw his weight behind anyone opposed to Walker, including Costa Rica's president, Juan Rafael Mora. With Vanderbilt's backing, Mora assembled an |  army and marched north. A Nicaraguan invasion at Santa Rosa, Costa Rica, in March ended in defeat for Walker's forces. When the Costa Rican units defeated Walker's men at the Battle of Rivas they were accompanied by mercenaries recruited by Vanderbilt as well as his material support. Vanderbilt's agents also worked to cut off supplies to Walker's forces. At one point they captured the steamers on the Río San Juan. They also offered free trips to the United States for Walker mercenaries who deserted. The British government also was no friend of Walker and applied military pressure. Despite the Battle at Rivas, Walker, managed to have himself inaugurated as president of Nicaragua in July and worked to Americanize the country. He decreed that English would be the official language and welcomed settlers from the United States. Much has been written about Walker's pro-slavery leanings. Stephen Dando-Collins credits practicality instead of philosophy in the 2008 "Tycoon's War: How Cornelius Vanderbilt Invaded a Country to Overthrow America's Most Famous Military Adventurer." He said that Walker embraced slavery and threw out Nicaragua's emancipation edict because he needed support from U.S. Southerners. Vanderbilt also was supporting anti-Walker efforts by Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Eventually it was illness in the form of cholera that ravaged Walker's army, and he surrendered to a U.S. Navy officer who sent him home. Walker tried again in 1860 but he was captured and shot in Honduras. Next Thursday, the anniversary of the battle, also is called the Día de Juan Santamaría, It is a public holiday, which means most employees are off with pay. |

.

0 comments:

Post a Comment